To be or not to be derivative

A guide to creating a work with multiple CC-licensed sources

It is often the case that, even if are creating something new, we will make use of existing works to supplement or improve our own works. This can be the simple use of an image to improve the esthetics of an article, or even building a documentary film around archive footage and sounds recorded entirely by others. But one obvious stumbling block here is that we have to expect that all works not in the public domain are protected by copyright and thus not suitable unless our usage falls under fair use (or fair dealing). Creative Commons licenses solve this problem by clearly stating what we can and can't do with a given work. The prevalence of these licenses consequently means we now have access to a myriad resources, all of which we can use without fear of violating copyright law.

Nevertheless, because there are different CC licenses, it's possible for people to become confused when it comes to creating a work that incorporates multiple CC-licensed works, especially if these sources are licensed differently. Another issue is using works licensed with the ND (NoDerivatives) clause. When is a usage permissable, and when does it count as derivative? This confusion results in creators avoiding ND-licensed works, or otherwise recklessly using them as though they were licensed differently.

If you're one of these people, then read on! In this guide, we will look at some examples of what counts as a derivative work from multiple sources and what only counts as a collection of works. We will also discuss creating a work that is wholly made up of other works, and how to attribute it appropriately.

An adaptation and a collection

In CC licenses, NoDerivatives specifies that a reuser is not allowed to create an adaptation or modification of the work—in other words, to create a derivative work—unless it is for personal use and will not be shared. The term “adaptation” has different meanings in different countries, depending on their respective copyright laws.

In the case of Indonesia's copyright law, for example, in the elucidation of Article 40, Section 1.n states that “adaptation means the transformation of a work into another form. For example, a book adapted into a film.” This is a relatively loose definition of an adaptation. Nevertheless, in general, a work can be considered an adaptation when it has gone through enough modification that the resulting modified work shows enough originality to itself be copyrightable. If a work is a mere combination of works from multiple sources, in full or partially, with the content unchanged in any way, then it is not an adaptation and does not count as a derivative work, even when it is presented in a different format or medium. This work is normally called a collection.In short

An adaptation is created when you modify the content of a work or remix the (modified) content of multiple works.

In such cases, you must attribute the original works and indicate what changes you made. Creative Commons licenses with the ND clause may not be used.

Examples include translations, music videos, photoshopped images, and films based on books.

Combining works Licensing a derivative workA collection is created when you combine multiple works with the content unchanged.

The original works must still be attributed, but you of course don't need to note any changes. All CC-licensed works can be used, as long as you follow the sharing and noncommercial requirements stipulated in each of the original works.

Examples include anthologies and mixtapes.

Licensing a collection

Putting theory into practice, featuring Mimi and Eunice

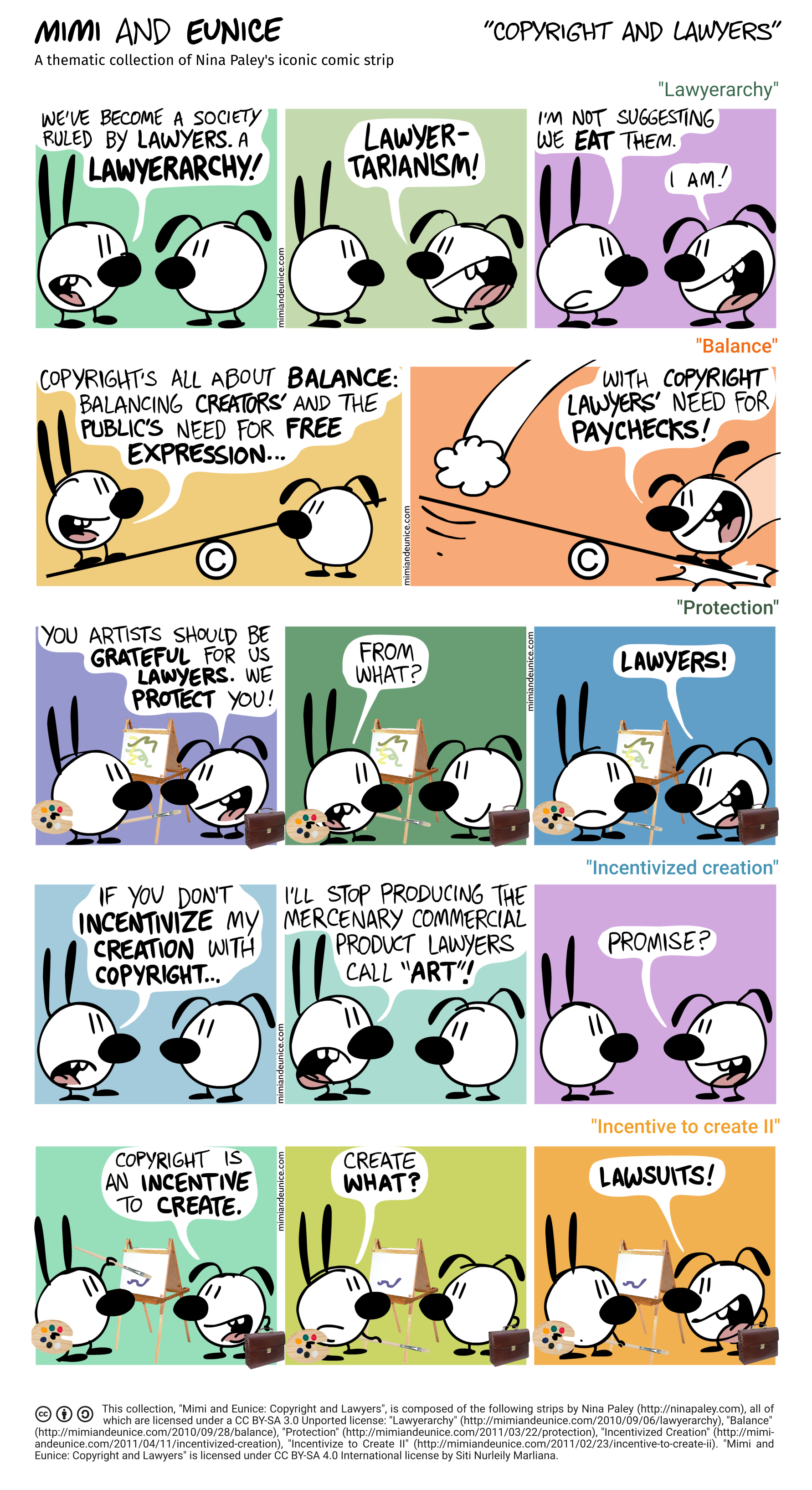

Understanding the difference between an adaptation and a collection should be simple enough now, but let's put this understanding into practice with some real-world examples. For this, we decided to borrow from Nina Paley’s satirical comic strip, Mimi and Eunice, which is licensed CC BY-SA.

To illustrate a collection, we've taken five topically-related strips and combined them to create a single comic called Mimi and Eunice: Copyright and Lawyers (Figure 1). These five strips are used as is; nothing is changed from the originals, and this therefore does not constitute an adaptation. As such, the type of CC license used in the original work does not matter—even if it uses a license with ND—as long as the author is credited appropriately and the terms of their license are followed.

Because we didn't modify the content of the strips, we don't need to use the same license Nina used (CC BY-SA), and can choose a looser license (such as CC BY), because we are applying the license only to our work, not Nina's. Nevertheless, we decided to license our collection CC BY-SA out of respect for the author.

Now, consider that Mimi and Eunice is written in English. What if we want to introduce the comic strip to an Indonesian audience? To achieve that, we need to translate it into Indonesian (Figure 2). Translation of a work is a form of adaptation. That means that if we want to share a translation of Mimi and Eunice publicly, we need to first ensure that is not licensed CC BY-ND or CC BY-NC-ND. Thankfully, it is not! So, we can happily proceed with our translation, modifying the text in the images.

Figure 2 is essentially the same as Figure 1; the sole exception is the language. But this now counts as an adaption, and we have to attribute accordingly, stating the author of the original work (Nina Paley) and what has been changed (the language). Additionally, because this is a modification, we now need to abide by the SA (ShareAlike) clause in the CC BY-SA license used by Nina, and license our new translated version similarly.

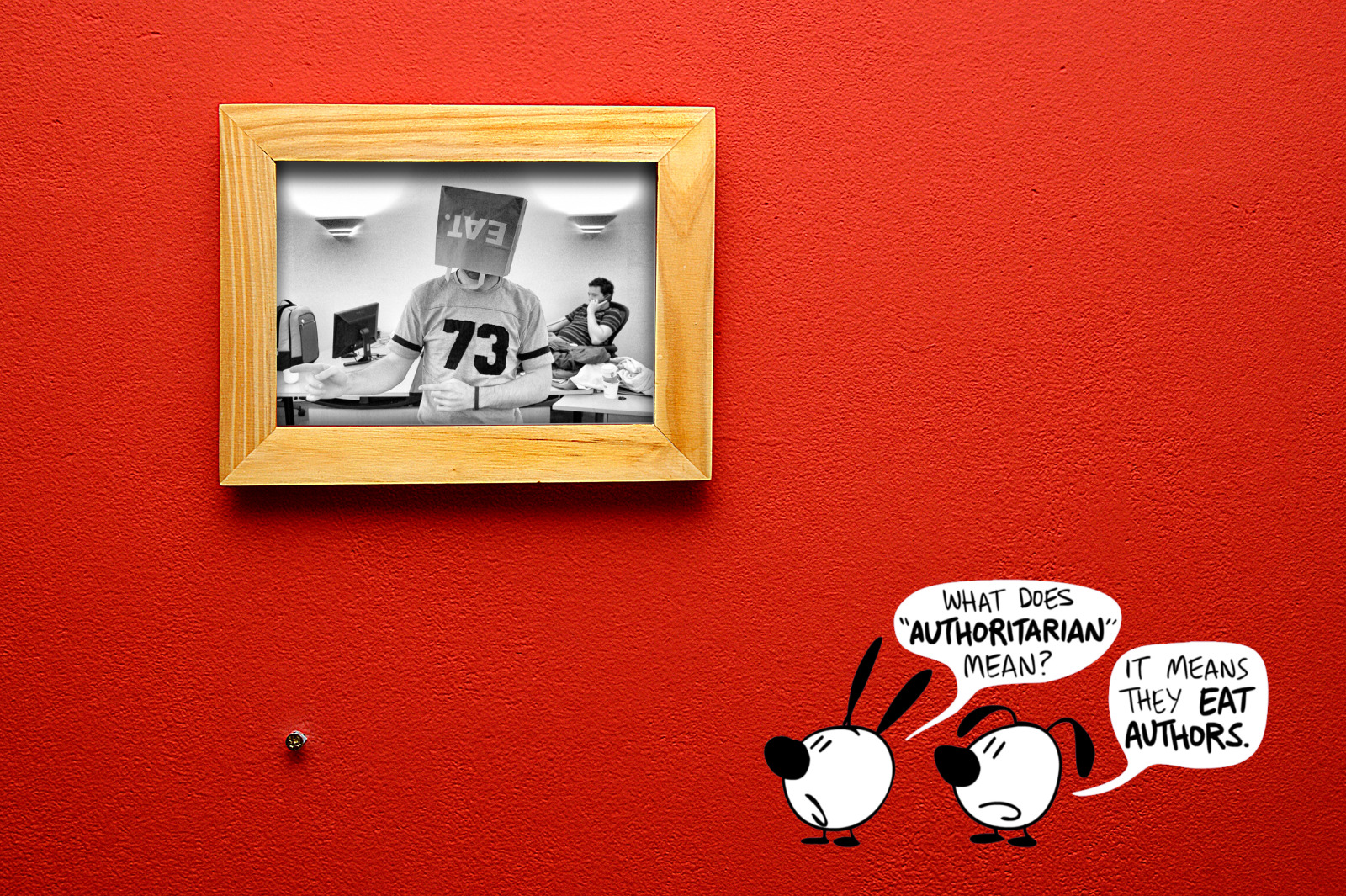

Another example of an adaptation is a remix—combining works from several sources. A simple remix, which is once again based on a panel from Mimi and Eunice can be seen in Figure 3, where we combined a walled background with a frame, a photo of a man with a bag on his head (modified to be grayscale and higher contrast), and Mimi and Eunice commenting on what they see (modified to show only Mimi and Eunice). These images are licensed CC BY, CC BY-SA, and CC BY-SA, respectively.

Because at least one of these original works use the SA clause, we must license our new remix accordingly.

Remember proper attribution with TASL

Regardless of the licenses involved, we must always respect the rights of creators, crediting them appropriately and abiding by the terms of their chosen license. Still, while creating an attribution for our own work is a simple process, doing so for a collection or adaptation can be quite daunting and meticulous. But fear not! All it takes is remembering TASL: the title of the work, the author of the work, where you found the work (the source), and the license of the work.

By using the TASL method, you can systematically build your list of whom to credit and how; all that remains after that is noting what modifications you made (if any). It's that easy, and also what we used to write our own attributions in this guide.

Siti Nurleily Marliana and Joaquim Baeta. This guide is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.